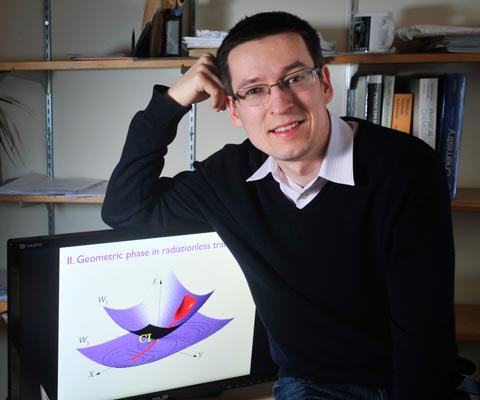

John Zilcosky

From Plato to Hulk Hogan: Researcher tells the surprising tale of wrestling

There’s more to wrestling than meets the eye, and University of Toronto researcher John Zilcosky is writing a book to share the fascinating story with the world. His work on the project, Wrestling: A cultural history from Plato to Hulk Hogan, is supported by a 2022 Guggenheim Fellowship.

A professor of German and comparative literature, Dr. Zilcosky argues that wrestling – as the world’s oldest sport – was crucial to the birth of civilization.

“One of my arguments is that Plato actually saw the importance of wrestling in developing a rational society…unlike any other sport, wrestling encapsulates the violence that we do to each other.”

His book will explore why we wrestle and why wrestling was humanity’s first sport. Dr. Zilcosky will trace its history from early civilizations through the classical, Renaissance and modern eras to today’s ‘pro’ wrestling industry. He will explore wrestling’s presence in Indigenous cultures and with women practitioners.

“In this first book examining wrestling’s historical arc, I argue that its defining quality is the simultaneously staging and containing of both violence and sex: Two men embrace aggressively yet do not kill or rape the other,” he says. “We watch as people try to hurt and not hurt each other, personifying the ambivalence that made us human.”

Dr. Zilcosky grew up as a competitive wrestler and competed with Harvard as an undergraduate. He calls the research project a “labour of love” and hopes his new book will resonate with a diverse audience and catalyze new thinking about sport and civilization.

On winning the Guggenheim, he says it’s encouraging because so much of his work is done in isolation. “So to be recognized by a major foundation, like the Guggenheim, it just gives you as a researcher this sense that other people care, that your work is important. It allows me to take risks I might not normally have taken and to make my project even more ambitious, to really say things about how wrestling is connected to the dawn of civilization itself, and what it means to be human – things I might have been a little too shy to say without the encouragement of a foundation like this.”

Astronomer explores origin of planets

Winning the 2022 Guggenheim Fellowship is helping Yanqin Wu, a professor of theoretical astrophysics in the David A. Dunlap department of astronomy and astrophysics, advance her research exploring how planets form around stars.

“As astronomers, we like to understand how everything in the universe comes about and for me my main interest is in understanding how planets come about, the origin of planets,” she says.

Dr. Wu’s work focuses on protoplanetary disks – disks of gas and dust that that surround young, newly formed stars. She is currently investigating an aspect referred to as segmented disks.

Throughout her career, Dr. Wu has studied planets within and beyond our solar system. She uses data from the Kepler planet-hunting space telescope and other observing programs to examine their structure, movements and formation.

“We are basing our theories on data from the biggest telescopes and biggest observatories in the world,” she says. “For example, we used a lot of data from space missions.”

Dr. Wu says the benefits of astronomy are often overlooked or misunderstood. “First and foremost is that we are human, so we are interested in the world; we have native curiosity,” she says.

“And if we don’t pursue our curiosity, we are a rather boring species.”

Learn more about the Guggenheim Fellowship

Unlocking the mysteries of real-world memories

How exactly does the brain form memories of real-world experiences? That’s a question Peggy St. Jacques is working to answer, now with the support of a 2022 Sloan Fellowship.

“I’m looking at memories for real world events, at how the brain supports how we form these real-world episodic memories,” the University of Alberta psychology professor explains. “We know quite a lot about how the brain supports how we remember those experiences, but we can’t actually interrogate what’s happening in the brain when people are outside in the real world. However, now with developments in technology, we can actually bring the real world into the lab.”

Making that happen is the focus of Dr. St. Jacques’ Sloan Fellowship-supported research. Her team is producing 360-degree videos of real-world events in order to create immersive virtual reality environments.

“Our lab is using an MRI-compatible virtual reality headset that will present the videos in 3D and create an immersive experience… So people will have a first-person perspective on this event, as if they’re in the real world, but they’ll be in the MRI.”,” she says. “We’re looking at the neural activity in their brain, as they’re experiencing these events, and then we can assess their how they’re forming memories for those experiences.”

Impairments in real world memories are at the heart of disorders like Alzheimer’s disease, she says, “but we really don’t know how the brain is supporting the formation of those experiences. I’m hoping that the basic understanding that we might gain could inform those types of impairments and other disorders of related to real world memories such as PTSD.”

Dr. St. Jacques says she is honoured to receive “such a prestigious award” as the Sloan Fellowship. Funding from the award will support hiring personnel for the lab and MRI costs.

Swedish-Canadian composer creates new music using live electronics controlled by AI

Örjan Sandred, professor of composition at the University of Manitoba, has won a 2022 Guggenheim Fellowship in support of a project in live electronics controlled by artificial intelligence. The Swedish-Canadian composer is collaborating with the Stenhammar String Quartet on the composition.

Many of Dr. Sandred’s works reflect his search for new methods of composition, including Rule-based Computer Assisted Composition techniques, where the computer acts as the composer’s assistant. His pieces involve live electronics and sometimes live video processing. These methods use microphones and video cameras to create a counterpoint between visual and aural stimuli.

He says artificial intelligence has led him to investigate further how musical parameters such as pulse, rhythm, pitch and timbre interact to create powerful musical expressions. “Music ultimately takes place in our brain, that’s why I believe music is a great tool to deepen our understanding of the human brain. Music structures reflect how the brain works.”

Through a commission from the Manitoba Arts Council for pianist Megumi Masaki, Dr. Sandred just completed a pre-study for his Guggenheim project, where he explores how a computer can learn the style of a piano performance by using Self-Organizing-Maps, and then base its musical response on those findings.

Dr. Sandred’s music is available on the CDs Sonic Trails (2020) and Cracks and Corrosion (2009). The second edition of his book, The Musical Fundamentals of Computer Assisted Composition, is now available.

To build trust, researcher finds errors in AI

For artificial intelligence (AI) to reach its potential in benefits to society, people have to trust it. Building up that trust is the focus of Computer Scientist Nicolas Papernot’s research, now supported by a 2022 Sloan Fellowship.

“I basically study the intersection of AI or machine learning with computer security, privacy and trust in general,” the University of Toronto professor explains. “We’re trying to understand when machine learning algorithms fail, so that we can improve the trust that we humans and society in general have when deploying these machine learning algorithms, and essentially relying on their prediction.”

For example, machine learning is used to recognize our voice when we talk with virtual assistants on phones or smart speakers. “And what we found in one of our projects is that if you speak through a tube to the voice assistant, then it will recognize your voice as being the voice of another person. You can even choose the length of the tube, to induce the model in thinking you’re a specific person.

“That basically shows that the models have very different ways to recognize patterns in the data that they process than we would as humans. And so there’s this kind of semantic gap between how they make predictions and how we’re able to exploit that if we’re malicious entities.”

In another example, Dr. Papernot’s team was able to demonstrate that under certain conditions, an image classifier would recognize a stop sign as a yield sign.

His work is about understanding what needs to change about the algorithms to fix these issues. It aims to resolve security and privacy issues that undermine our trust in AI. The public’s reservations about the technology can limit applications in important areas like medicine and public services.

“When we apply machine learning, we currently have a poor understanding of when we can trust that the predictions are correct. So that’s one important reason why we are working on this, to basically have either failsafe mechanisms that we can rely on knowing that the prediction is going to be incorrect, or to ensure that we are actually making a correct prediction.”

Dr. Papernot says winning the Sloan Fellowship is “very humbling.

“It also gives me confidence that we can continue looking for problems that are higher risk in terms of the research that we’re trying to do,” he says. “Because that eventually is how we make the most progress. And so having this external validation that we’re thinking about the right problems is always helpful when we’re taking a bit more risk.”

Researcher honoured for changing lives through innovative education projects

In recognition of her longstanding commitment to education as a means of transforming the lives of youth, especially those from marginalized backgrounds, McGill University Professor Claudia Mitchell has been awarded the 2022 José Vasconcelos World Award of Education.

The award jury highlighted Dr. Mitchell’s work in tackling difficult social issues impacting girls in various countries and her success in running innovative and adaptive projects, in addition to teaching and research.

“I’m very interested in social justice issues,” says Dr. Mitchell. “So I do a lot of work around gender equity, gender-based violence and getting more girls into school, but also how do we involve boys and young men in gender equity issues.”

Her projects often involve filmmaking, primarily using cell phones to make videos. “We also do a lot of work around photovoice, photography, drawing – really looking at issues that are very difficult to put into words, but are often perhaps more powerful to try to visualize.”

Community outreach is central to Dr. Mitchell’s research. “It is very important to facilitate dialogues and work with communities.”

Much of her work takes place in Sub-Saharan Africa. “Right now we’re doing a lot of work in Sierra Leone, where there are particular critical issues around gender,” she says.

On winning the José Vasconcelos World Award of Education, Dr. Mitchell says it reinforces the value of her work. It also signals to young researchers that this kind of research, that sometimes brings about change by working with small numbers of people, is worth pursuing.

For example, she says, “there was a project in South Africa where 10 girls made cell films about forced and early marriage, and members of the community saw those cell films. The chief of the community, along with other stakeholders said, ‘we have to do something.’ And they actually went to the legislature in Pietermaritzburg, and passed a protocol about forced and early marriage in one district.

“So that kind of impact and having people see that, bringing that out as evidence of the value of this kind of work, is really important.”

Learn more about the José Vasconcelos World Award of Education

Navigating an uncertain future: SFU researcher explores how society copes with challenges

Human geographer Geoff Mann won a 2022 Guggenheim Fellowship in support of his work on the politics of climate change. A professor in Simon Fraser University’s Faculty of Environment, Dr. Mann is exploring the uncertainty that we face today, especially around climate change, and how our attempts to manage that uncertainty – politically, economically, institutionally and culturally – are changing.

“I’m really interested in what at the broadest level you might call the problem of uncertainty. We’re in this moment, especially with the problem of climate change, where the future seems less and less manageable, and the past seems a less and less helpful set of tools to address it because the future is increasingly unlike anything we’ve experienced before.”

Dr. Mann is examining the way that economists, policymakers, scientists and politicians are trying to cope with this uncertainty. He thinks that much of the “far right reactionary” sentiment is driven by a desire to stop time, to return to a place that was more comfortable for some.

“I’m interested in capitalism,” he says, “the theory of it, the history of it, the politics, the economics. And lately that has turned to the problem of the relationship between capitalism and climate change and the way that we’re trying to use economic thinking as a way to manage or produce policy to confront the problem of climate change.

“I’m pretty big critic of the role of some climate economics in that I think it’s actually functioning as a kind of a palliative,” he adds. “It’s making us feel a lot less worried than we should be and suggests to us that we have answers that are actually nowhere near powerful enough to address the problem.”

In recent years, Dr. Mann has been writing in the popular press about what he sees as standard economic approaches to everything from inequality to monetary policy and climate change. With support from the Guggenheim Fellowship, he’ll be working on a new book about society’s frustrated attempts to manage the uncertainty of the moment.

Research on the mathematics of shape recognized by Sloan Foundation

Alexander Kupers’ research on the mathematics of shape, known as topology, has garnered the University of Toronto Scarborough mathematician a Sloan Fellowship.

One of the surprises in topology, he says, is that simple shapes, such as discs and spheres, can have complicated symmetries.

“The idea is that if you understand the symmetries of some shape, you understand that shape really well,” explains Dr. Kupers. “And you can use those symmetries to help you understand all the problems that the shape is involved in.

“When you study these, especially in high dimensions, you realize that there are a lot of interesting connections to other parts of mathematics and to theoretical physics.

On winning the award, Dr. Kupers says, “It’s an honour to win a prize like that. Many excellent mathematicians have gotten Sloan Fellowships in the past.”

He plans to use funds from the Sloan Fellowship to hire more postdocs and create a more supportive research environment for PhD students on his research team.

Learn more about the Sloan Research Fellowship

Quantum materials researcher wins only Guggenheim Fellowship in physics for 2022

In recognition of his work on the novel properties of quantum materials, University of Toronto Professor Yong-Baek Kim has won a 2022 Guggenheim Fellowship. Dr. Kim, director of the university’s Centre for Quantum Materials, works in theoretical quantum condensed matter physics. This involves the study of matter and its exotic behaviour when quantum mechanical electrons are subjected to extreme conditions, such as low temperature and high pressure.

“What we are doing is basically trying to understand emergent physical properties that cannot be easily understood,” he says. “There are actually many materials where interaction between electrons is fundamentally important, and even if you understand the motion of the single electron, you cannot predict the motion of many, many electrons.”

His research has potential applications for various quantum technologies, including quantum computing. His main contributions include theory of quantum spin liquids in quantum materials with strong spin-orbit coupling and theoretical proposals for experimental detection of novel quasiparticles in topologically ordered quantum phases, which may become useful for future quantum technologies.

Dr. Kim was the only researcher to be awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in physics for 2022.

Astrophysicist studies mysterious Fast Radio Bursts

McGill University Professor Victoria Kaspi, a world leader in the study of neutron stars, has won the 2022 Albert Einstein World Award of Science. Dr. Kaspi, director of the McGill Space Institute, has helped position Canada as a world leader in astrophysics.

The Einstein World Award is largely in recognition of Dr. Kaspi’s work on magnetars – highly magnetized, young neutron stars that suffer large x-ray and gamma-ray explosions.

“They’re very dramatic, very interesting objects,” she says. “I loved studying them and I studied them for at least 15 years.”

More recently, Dr. Kaspi’s research is focused on Fast Radio Bursts (FRB), which come from far outside our galaxy. FRBs are transient radio pulses varying in length from a fraction of a millisecond to three seconds. They are caused by an astrophysical process not yet understood. FRBs are thought to release as much energy in a millisecond as the Sun emits over three days.

Dr. Kaspi leads the CHIME Fast Radio Burst Project, which uses the CHIME telescope and has discovered more FRBs than all other radio telescopes combined.

On winning the Einstein World Award, Dr. Kaspi says it’s sometimes “uncomfortable” being singled out for recognition, since her work is such a team effort. “But the fact is that having these recognitions does bring many tangible benefits to my research program and I think, by extension, to Canada’s research profile overall.” That includes, she notes, making it easier to recruit students and postdocs to her team.

“And I think that raises the bar for everybody, bringing fantastic people into Canada who may never have come here otherwise. And then sometimes they end up settling here and developing research programs of their own. That’s a wonderful thing for the country.”

Learn more about the Albert Einstein World Award of Science

Computer scientist advances applications of geomtry processing

In recognition of his contributions in geometry processing, University of Toronto computer scientist Alec Jacobson is a 2022 winner of the Sloan Fellowship. Geometry processing is a field with applications ranging from climate simulation and biomedicine to robotics and architecture.

“It’s all about how to represent two-dimensional and three-dimensional shapes on the computer and manipulate those shapes, analyze those shapes and put them, hopefully, to some human use,” he explains.

“Geometry processing has its roots in computer graphics, where those shapes might be characters or scenery and visual effects or computer games. But we also find applications in computational fabrication or the design of physical things around us – including in health care and medical sciences, when we represent the anatomies of people’s bodies or body parts.

“The idea is to make sure that the algorithms that we create work on messy data that we collect in the wild, and we have great ways of collecting 3D geometry. Now, even just with our cell phones, we can collect 3D data. But unfortunately, that’s very noisy, and it can lead to problems with existing algorithms. So a lot of our work is in making sure that those work correctly even if the data is messy.”

On winning the Sloan Fellowship, Dr. Jacobson said it was a big surprise, because he had applied a few times in the past and didn’t win.

“It’s always a bummer to get rejected,” he says. “They had changed the rules with regards to how many years out from your PhD you could be, and I was able to apply again. So it was really fantastic to be able to win and kind of a head-spinning experience to look at the previous winners and see sort of what I need to live up to.”

He plans to use funds from the fellowship “to pay PhD students and to pay them competitively.” The financial support will also be helpful, he says, in allowing him and other members of his research team to attend conferences to disseminate their research.

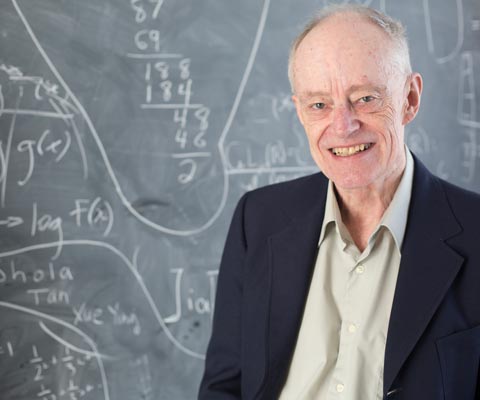

Pioneer in AI seeks new kind of deep learning algorithm

Artificial intelligence pioneer Geoffrey Hinton won two major international research awards in 2022: the Royal Society’s Royal Medal and the Princess of Asturias Award for Technical & Scientific Research. The University of Toronto Professor Emeritus shares the Princess of Asturias Award with three other leaders in the field of artificial intelligence known as deep learning: Yoshua Bengio (Université de Montréal), Yann LeCun (New York University) and Demis Hassabis (DeepMind).

His groundbreaking work in deep learning – a field of artificial intelligence that mimics the way humans acquire some kinds of knowledge – has driven advances in many areas.

“I’m trying to figure out how the brain learns,” he says of his research. “And one consequence of that is that various attempts to understand how the brain might be learning turned out to be useful for engineering.

“In particular, there’s an algorithm called backpropagation. And that’s how nearly all the large neural networks are now trained.” Backpropagation started off as an idea about how the brain might acquire knowledge, he says, but now it’s not clear whether the brain actually does backpropagation.

“I suspect that the brain doesn’t do backpropagation,” he says. So I think the technology we’ve got now is working in a different way from the brain. But it’s certainly very useful for engineering. And all of these large language models and large vision models use backpropagation.”

Dr. Hinton explains that backpropagation only works if the neural network has a perfect model of itself. “I think the brain doesn’t,” he says.

“And also analog hardware wouldn’t. So if we want to learn in analog hardware, we’re going to need a different kind of algorithm.”

That answer to that problem is the focus of Dr. Hinton’s current research.

“The question is, what kind of learning algorithm can use [analog hardware]? The brain obviously has a pretty good learning algorithm, but possibly not as good as what we now have for these deep neural networks.

“So for a long time, the aim was to make artificial neural networks work as well as real ones. And I suspect that quite soon there’ll be working better than real ones.”

Dr. Hinton is also chief scientific adviser at the Vector Institute for Artificial Intelligence and a vice-president and engineering fellow at Google. He won the Turing Award, often referred to as the ‘Nobel prize of computing,’ in 2018.

Learn more about the Royal Society’s Royal Medal and the Princess of Asutrias Award

Anthropologist explores roots of global movement in Indigenous political activism

With support from a 2022 Guggenheim Fellowship, Anthropologist Michael Hathaway will be dedicating a year to advancing his research on the rise of Indigenous networks in the Pacific Rim.

Director of the David Lam Centre for Asian Studies at Simon Fraser University, Dr. Hathaway studies global environmentalism and Indigenous rights in Asia. He is currently researching a series of all-Indigenous delegations in the 1970s that travelled to China from Japan, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The Indigenous groups returned to their home countries inspired to challenge colonial systems.

The visits were at the invitation of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Leader Mao Zedong, explains Dr. Hathaway. “He invited a delegation from Canada, three delegations from Japan, a delegation from Australia, and one from New Zealand.” And around the world, emerging activists in Indigenous communities started reading the Little Red Book – a collection of quotes from the CCP leader that promoted the Maoist version of socialism.

“He tried to convince them that in China, the people he referred to as “ethnic minorities” actually had the best situation of anywhere in the world. Delegates visited a well-funded university where ethnic minority professors taught ethnic minority students, and read books in their own languages. There was nothing like this that existed in the delegates’ own countries. And so they were often very impressed.”

The visits started to change their perspective, says Dr. Hathaway. “Rather than thinking very locally or nationally, they started to understand themselves as global citizens.” Some groups later hosted other delegations in their home countries to advance their shared work.

Today in New Zealand, where Dr. Hathaway is spending several months researching that country’s experience with the movement, there are only a few survivors from a 1975 trip to China. Hathaway is trying to understand how the visit transformed the delegation’s political strategies, priorities and agendas.

In Japan, the delegation to China started language revitalization efforts when they returned. Around this time, in Canada, under the leadership of George Manuel, a member of the Secwepemc Nation in British Columbia, the World Council for Indigenous People was created, fostering this movement.

Dr. Hathaway’s work in New Zealand has resulted in an unexpected side benefit: access to archives about events in Canada. “It’s interesting that in New Zealand, I’ve been able to find archives by Maori about events in Canada that are not in the Canadian archives.”

Physician scientist recognized for advancing quality in research

McMaster University Professor Gordon Guyatt’s pioneering work in evidence-based medicine (EBM) has garnered him the 2022 Einstein Foundation Award for Promoting Quality in Research.

Dr. Guyatt, a physician who coined the term evidence-based medicine, is ranked as one of the world’s most-cited scientists. He published his first description of EBM in a 1991 paper. Today the term is used worldwide to describe health care based on the highest quality, current evidence available.

“In evidence-based medicine you need systematic reviews of the best evidence to guide your practice,” he explains. Dr. Guyatt has been at the forefront of developing the methods to do good systematic reviews.

“That’s another way of raising the quality of research.”

Dr. Guyatt also played a key role, along with Andrew Oxman from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and McMaster professor Holger Schunemann, in the development of the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) approach to medical research.

GRADE is a framework for developing and presenting summaries of evidence and a structure for moving from evidence to clinical practice recommendations. This approach has improved patient care by allowing health care providers to access clear and concise recommendations about the treatment of a given condition.

Dr. Guyatt’s work in improving research also includes major contributions to the quality of randomized clinical trials and measuring patients’ health status.

The GRADE approach is used by more than 110 organizations worldwide, including the World Health Organization.

Learn more about the Einstein Foundation Award for Promoting Quality Research

Pure math researchers see long game for applications

“I would compare it to philosophy in a way,” Professor Michael Groechenig says of the development of the field of algebraic geometry over centuries. “The problems we’re working on, they come from somewhere. The research community kind of arrived at those problems over the course of a long process – there’s a certain history to them. And it’s a field that has changed drastically over the past century or so.

“Applications exist,” says the University of Toronto mathematician. “But, you know, it’s a small percentage of mathematical research that leads to applications. However, when there is an application, it’s usually quite important.

“Very often when those applications are found, it’s not just decades later, but even centuries later. And so in a way, I feel like the purpose of a pure mathematician like me is also to preserve this knowledge and to make sure that we don’t forget that we can lose this skill; it’s a means of keeping the tradition alive, and to pass it on to future mathematicians, and also, possibly future engineers, or other people who might be working on applications.”

Dr. Groechenig’s research focuses on moduli spaces.

He says winning the Sloan Fellowship is special because it’s validation from fellow mathematicians, to a certain extent.

“Once in a while, it’s nice to receive a tap on the shoulder to say something’s well done. Sometimes there are big stretches of time where you receive very little feedback. Failure is part of the research; it happens constantly. And so sometimes it’s nice that certain achievements are recognized by your peers.”

Photo credit: Drew Lesiuczok

Pioneer in study of landscape fragmentation wins BBVA Frontiers of Knowledge Award

Lenore Fahrig, Professor of Biology at Carleton University, won the prestigious BBVA Frontiers of Knowledge Award in 2022 for her contributions to the field of spatial ecology. Dr. Fahrig studies the impacts of habitat fragmentation – and the loss of connectivity between remnant patches – on biodiversity.

She shares the BBVA Award, worth 400,000 EUR, with two other ecologists, Simon Levin and Steward Pickett, for incorporating the spatial dimension into ecosystem research.

Dr. Fahrig’s research on landscape fragmentation addresses practical questions: Is it better to create one large, protected area or many smaller ones? Should we create ‘ecological corridors’ between protected areas? How does the layout of roads impact ecosystems?

She “has developed theory-driven and data-proven ways for effectively reducing the effects of habitat loss by means of connectivity conservation,” says the awards committee. “Her work recognizes the critical role that road networks and small conservation areas play in altering the distribution and abundance of species.”

Dr. Fahrig’s work shows that small patches of protected land have value. This conclusion stems from her research on the impact of landscape structure on abundance, distribution and persistence of organisms. Since landscape structure is strongly affected by human activities such as forestry, agriculture and development, the results of her research are relevant to land-use decisions.

“There is a lot of intuitive thought about larger species or those endangered doing better in a larger block, such as species that do better in the interior of a forest,” she says. “This seems to make sense because if you have 10 small blocks you have more of the edge and less of the interior area of the forest that those species need. Some people think that means there would be more species in a bigger block than many small ones.

“This is a problem because if we assume that small parcels of habitat have low value for biodiversity, we can end up with thousands of small patches that have no protection, even though they host a great deal of biodiversity,” she says. “If they are destroyed the loss to biodiversity is huge.

Dr. Fahrig initiated new sub-fields including connectivity conservation. Hundreds of organizations around the world have used her research to refine their conservation policies and practices.

In 2021, Dr. Fahrig won the Guggenheim Fellowship.

Learn more about the BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award

Computer scientist pursues generative models in deep learning

David Duvenaud, assistant professor in computer science at the University of Toronto, has been awarded a 2022 Sloan Research Fellowship in support of his research in deep learning.

He says the goal of his research is to build generative models, as opposed to simply decision-making classifiers or predictors, because generative models can, in principle, answer any question about the domain, in addition to classification or predicting.

“For example, in a medical setting, we could build a classifier that predicts the probability of a disease given all the data we’ve seen about the patient,” says Dr. Duvenaud. “But if we instead built a generative model, we could ask for the joint probability of more than one disease at a time or ask to see what representative data for patients with the disease looks like. This helps us check the quality of the model, and also lets us make more sophisticated decisions.

He says a generative model also usually makes it easier to incorporate many kinds of data.

Dr. Duvenaud plans to use funds from the Sloan Fellowship, which is an unrestricted research gift, to support his group’s development of “deep, natively continuous-time models.”

“The standard approach to handling data that comes through time, such as medical records, has been to divide time into discrete bins, and somehow average all the data together within a bin,” he says. “This is usually pretty fast and simple. But it unfortunately requires that we somehow squash the data into a pre-specified format before the model can even look at it. Instead, we’re building models that can directly ingest data in a much rawer format. This requires a bit more thought into the model setup, and making them generative also requires an extra step, called ‘approximate inference.’ But I’d argue that we were previously pushing much of that complexity onto the users of these methods by forcing them to do their own pre-processing. In a sense, we’re trying to automate more of the scientific modeling pipeline.”

On winning the Sloan Fellowship, Dr. Duvenaud says he had “made my peace two years ago with never getting it, since I had aged out of eligibility. But they changed the rules last year to allow anyone pre-tenure to apply. Mainly I am thankful to my letter-writers, who I felt bad about asking for time-consuming favours.”

He says these kinds of awards are useful for “giving non-insiders a rough idea of who is seen as productive and impactful in a field.”

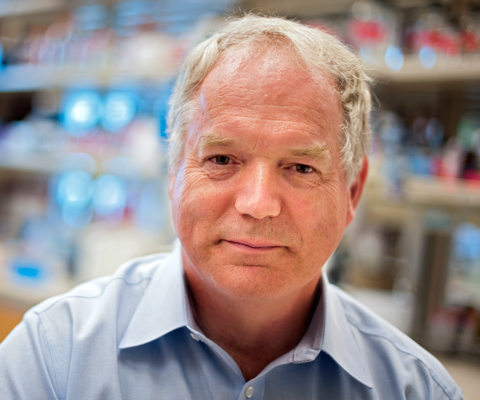

Researcher changed how we understand and fight cancer

John Dick, a world-renowned pioneer in cancer stem cell biology, has won the 2022 Canada Gairdner International Award. His groundbreaking work on leukemic stem cells has transformed our understanding, diagnosis and treatment of acute myeloid leukemia.

“Basically, our research is about trying to figure out what makes a stem cell a stem cell, and how does it go bad,” says the University of Toronto professor.

For more than three decades, Dr. Dick’s work has revolutionized the understanding of normal and leukemic hematopoiesis. A senior scientist and Canada Research Chair in stem cell biology at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, his discoveries have changed views on the origin and nature of cancer and enabled new approaches to cancer therapy.

Dr. Dick made the first discovery of leukemia stem cells (LSC) in an acute myeloid leukemia patient. This finding established that cancer cells in a patient are not all equal; rather there is a hierarchy and only certain rare leukemia cells possess self-renewal, the key property of stem cells.

His discovery showed that “there’s only about one in a million cells that actually has the ability to regenerate leukemia when you transplant it in a mouse,” he explains. “And so that led to this whole idea that leukemia is just a caricature of normal development. You have one blood stem cell that can regenerate a large amount of blood; it’s a powerful cell. And it turns out leukemia works in a similar kind of way; there are rare leukemia stem cells that actually keep the cancer going.

“And when we began to study this in more detail, we realized that like normal stem cells these leukemia stem cells are also dormant or slowly replicating. This allows them to evade standard chemotherapy; they were the reason that leukemias look like they go away, but then they eventually come back from the surviving leukemia stem cells.”

Discovering that not every cancer cell is equal was, “a turning point for how we understand cancer, and how we study cancer.” It led to the exploration of cancer stem cells (CSCs) in other human cancers, such as breast, brain, colon, pancreas, skin and liver cancers.

Dr. Dick’s work highlights the need to ensure that CSCs are eradicated when therapy is delivered and the need for new therapies that target CSC vulnerabilities.

While he has spent all of his career in a research lab, Dr. Dick says the location of his lab when worked at SickKids in Toronto earlier in his career brought the meaning of his work into clear focus. His route through the building brought him past the hematology oncology ward.

“And you would see these kids, some of them were pretty sick, they don’t have any hair, they’re carrying the IV poles around. You would see the impact of cancer; it really focuses your mind. Every day, you walk through that, and you realize what you’re doing here is not just an abstraction, it’s not just solving a puzzle, it actually is about having an impact in the clinic.

“As we recognized that our work was having more impact, there becomes an imperative – we knew we had to keep going on this, because it was so important. That gives you a sense of urgency as well, because we need to do better. Too many people are still failing their cancer treatments, and we need to improve that.”

Biochemist’s work in lipid nanoparticles has the world knocking at the door

Over the course of his career, Pieter Cullis has received a number of international awards for his pioneering work that contributed to the highly effective COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, but his most recent, the 2022 Gairdner International Award, holds special meaning.

“It’s a Canadian award,” says the University of British Columbia biochemist and physicist. “So from that point of view, it feels really good because it’s recognition in your own country.”

Dr. Cullis shares the Gairdner International Award with Dr. Katalin Karikó, senior vice president of RNA Protein Replacement Therapies at BioNTech SE and an adjunct professor at the University of Pennsylvania, and Dr. Drew Weissman, director of the Penn Institute for RNA Innovation at the University of Pennsylvania. The three developed nucleoside-modified mRNA and lipid nanoparticle (LNP) drug delivery – the foundational technologies for the mRNA vaccines.

Drs. Karikó and Weissman discovered how to engineer mRNA, while Dr. Cullis developed the packaging system to effectively introduce the mRNA into the body.

For delivery of mRNA, the LNPs are designed to form a protective bubble and enable delivery to the interior of target cells.

Dr. Cullis has worked in lipid chemistry and the formation of LNPs over the past 40 years. New developments in his research aligned perfectly with the need for a COVID-19 vaccine, something he describes as “being in the right place at the right time.”

His work with LNPs also holds promise for cancer treatments, with the potential to develop highly personalized, relatively non-toxic kinds of treatments.

Currently, Dr. Cullis divides his time between UBC and pursuing commercial applications for LNPs and mRNA technology. Through Vancouver-based Acuitas, a start-up he co-founded in 2009, and NanoVation Therapeutics, a start-up he co-founded in 2019, Dr. Cullis and colleagues partner with pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, academic institutions and thought leaders from around the world to advance and commercialize mRNA therapeutics for a wide variety of diseases.

“Opportunities are coming out of it now because we have developed a well validated process to introduce nucleic-acid-based drugs into target cells in vivo,” he says of the mRNA and LNP technologies. “The world is really coming to us to develop the many new therapeutics this makes possible because we have this technology in place.”

The fastest measurements in the world: UofO researcher earns Wolf Prize for ground-breaking contributions to attosecond physics

Dr. Paul Corkum – a distinguished professor at the University of Ottawa, principal research officer at the NRC and co-director of the NRC-uOttawa Joint Centre for Extreme Photonics – is co-recipient of the prestigious Wolf Prize in Physics for 2022. He shares the prize with European physicists Ferenc Krausz and Anne l’Huillier.

Dr. Corkum is a pioneer in the development of a type of physics called attosecond science, which lasts one billionth of a billionth of a second.

“We’ve learned how to make the fastest measurements in the world; the fastest measurements that humans can make by a factor of 100 over what it was before,” he explains the work recognized by the Wolf Prize. “In the process, we found a way to force lasers to make soft x-rays, where you would not use lasers before – you would have used something more complicated before.”

“The third thing is we found that when you radiate materials with light, there is an extreme response that you can understand.”

“It’s really all about waves,” he says in offering an analogy to explain the research. “Think about going to the Bay of Fundy or the ocean,” says the native of Saint John, N.B., “and looking at the waves coming in. There might be seaweed on a rock, and you would see the wave pick the seaweed up and then return it with a crash onto the rock from which it left. So we’re going to do almost exactly the same thing with an atom. The wave, which is a light, is a wave of force on an electron – just like water is a wave of force on the seaweed moving it up and down. When laser light hits an atom, the electron is pulled free of the atom and it moves just like the seaweed would do before crashing into the atom from which it left, just like the seaweed crashes into a rock from which it left. If it gets caught, it gives out a flash of light. That would be like the bang of the seaweed against the rock.

“That flash of light is the very short pulses that I’m talking about,” he explains of the fundamental research. “So this is about high intensity light interacting with materials that can be atoms (we started with atoms) or it can be molecules; and we now know it can be transparent solids; and maybe even metals. We’re starting to look at metals.”

The son of a fisherman and tugboat captain, Dr. Corkum spent much of his youth around boats, sailing with his father and working on various types of engines. He says he owes his career to his high school physics teacher, Anthony Kennett.

“He told us that if you read an equation, it has to work out dimensionally. You have to think about what dimensions were involved in one side of the equation and what dimensions were involved in the other side of the equation; if it didn’t work out dimensionally; it wasn’t a good equation.”

“I thought, ‘This is really neat.’ And so, as we went through physics, I saw this as such a logical field that I liked very much.”

Computer scientist wins world’s largest science prize for work in quantum information

Université de Montréal Professor Gilles Brassard, a global leader in quantum cryptography, has been awarded the prestigious Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics – the world’s largest science award.

The computer scientist shares the three million USD Breakthrough Prize for 2023 with co-winners and colleagues, Charles H. Bennett (IBM Research), David Deutsch (University of Oxford) and Peter Shor (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) “for foundational work in the field of quantum information”.

In 1984, Prof. Brassard and Dr. Bennett, a chemical physicist, developed the first quantum cryptography protocol – an unbreakable encryption scheme – as a way to protect data communications.

The significance of their work became clear a decade later when Dr. Shor, a mathematician, discovered that a hypothetical quantum computer could penetrate the cryptographic systems currently used to protect Internet communications.

Data communications systems didn’t collapse following Dr. Shor’s discovery, because a quantum computer had not yet been built (as far as we know). But technology has rapidly advanced, Prof. Brassard notes, and a quantum computer will eventually arise. It’s no longer a question of if, but of when.

When that finally happens, quantum cryptography will be the only guaranteed way to protect online communications, including our financial information systems. Essentially, Prof. Brassard and Dr. Bennett had developed a cure 10 years before the ailment was discovered.

Today, “quantum cryptography is on the rise”, he says of the current impact of the discovery. “It’s more and more widely studied and implemented and used, even using real life now. Nobody would have predicted this 10 years ago.”

In 1992, Prof. Brassard and Dr. Bennett, along with their collaborators, including fellow Canadian Claude Crépeau, invented the theoretical concept of quantum teleportation. This phenomenon, confirmed experimentally by other researchers a few years later, is a fundamental pillar of quantum information theory.

Prof. Brassard was a mathematical prodigy, beginning a bachelor’s in computer science at the age of 13. His numerous past awards include the Wolf Prize in Physics, considered second only to the Nobel Prize, and the BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award in basic sciences.

Learn more about the Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics

More to a farm than meets the eye: McGill research explores multifunctional agricutlure

Elena Bennett, Canadian Research Chair in Sustainability at McGill University, investigates multifunctional agriculture in Canada. She’s driven by a desire to protect the iconic, but often overlooked working landscapes that provide biodiversity, places for recreation, flood control – even a connection to history and sense of place.

Dr. Bennett wants to know where the most multifunctional landscapes are in Canada and how they got that way. In 2022, her research garnered her a Guggenheim Fellowship.

“What I mean by multifunctional is agriculture that meets multiple needs or provides multiple benefits, which often sort of gets left behind when we think about agricultural landscapes,” she explains. “These are places that provide food, but they’re also beautiful to look at. And they store carbon to regulate climate change and retain nutrients in soil and are habitat for lots of different species, and can do all these other things. So one of the things that I’m doing is trying to investigate the magic about those multifunctional landscapes that allows them to do so many different things.”

The Guggenheim Fellowship will allow her to work on a book on the topic, while advancing her research. “The book may go a little bit more into the role of people as a force for good in the environment. We get a lot of this, ‘people are bad,’ at least in the environmental movement, a lot of thinking that the way to protect the environment is to block off some area and keep people out. But what I see when I look at some of these magic multifunctional working landscapes is not that there’s no people there, but that there’s a healthy relationship between people and environment.”

Dr. Bennett is co-chair of the international Programme on Ecosystem Change and Society and Founding Director of NSERC ResNet, a pan-Canadian network to improve management of working landscapes for the provision of multiple ecosystem services.

On winning the Guggenheim, she says it is “this great validation that what you’ve done is important, and what you’re proposing to do, at least by someone, is seen as being meaningful.”

Learn more about the Guggenheim Fellowship

‘Godfather’ of deep learning working to address gap in AI

“I’m as passionate as ever,” says Yoshua Bengio when asked what’s on the horizon for his research. “If we look at the current state of the art in AI, there is still, in my opinion, a big gap.” The unanswered questions, he says, centre on the mysteries of humans’ conscious thinking.

“It’s a gap that I and others think will not be filled by simply doing more engineering and having larger models, doing more computation and so on; there are some principles missing,” says the Université de Montréal professor.

“So this is driving my research. The hypothesis that we are exploring is that it has to do with high-level functioning. It’s about the things that you do consciously, things that you can verbalize.”

Dr. Bengio is the 2022 winner of the prestigious Princess of Asturias Award for Technical and Scientific Research, along with colleagues Geoff Hinton (University of Toronto), Yann LeCun (New York University) and Demis Hassabis (DeepMind) – regarded as the godfathers of deep learning.

He is founder and scientific director of Mila, the Quebec AI institute, a community of more than 1,000 researchers specializing in machine learning, and the world’s largest academic research centre for deep learning. Dr. Bengio also co-directs the CIFAR Learning in Machines & Brains program and is Scientific Director of IVADO, an AI research and transfer institute.

Deep learning uses neural networks for voice recognition, computer vision and language processing. It beat world champions at the most intellectual games and achieved a breakthrough in biology by learning how to predict protein structure from their sequence. Deep learning aims to mimic the functioning of the human brain, using algorithms to convert the biological process of learning into mathematical formulae that computers can implement. The goal is for a machine to learn from its own experience.

Dr. Bengio says that current deep learning is really good at doing things that humans do unconsciously, without having to think about them. But when it comes to the conscious thinking guiding our actions, there’s a kind of computation going on in our brains that scientists don’t yet fully understand.

“We have a lot of information, a lot of clues about the brain that have inspired deep learning, but in order to maybe propel the next generation of AI systems we should also incorporate these other attributes of human intelligence, of higher-level cognition, that currently, I think, are missing.”

His pioneering work in deep learning also earned Dr. Bengio the 2018 Turing Award, regarded as ‘the Nobel Prize of Computing,’ along with Dr. Hinton and Dr. LeCun.

Dr. Bengio says Canada’s growth and impact in AI has been impressive. “In terms of the growth of our AI ecosystem, and in terms of our scientific production, it’s been amazing. In the last few years, we’ve attracted some of the best researchers in AI from across the world.” The country’s position as a global leader in AI has been boosted in recent years by significant government investments in the field, he notes.

“Here in Montreal, we have a huge critical mass of these people – especially in deep learning, which is the part of AI that has been so successful and that industry is so excited about and investing in and deploying across many sectors of society.

Photo credit: Camille Gladu-Drouin

UBC researcher applies digital tools to pressing environmental problems

Karen Bakker, professor of geography at the University of British Columbia, leads the Smart Earth Project – an effort to map how the tools of the digital age are being used to solve pressing environmental challenges such as climate change and biodiversity loss.

It’s transformational research at the intersection of digital transformation and environmental governance; work that garnered Dr. Bakker the 2022 Guggenheim Fellowship, and was featured in her recent book: The Sounds of Life: How Digital Technology is Bringing Us Closer to the Worlds of Animals and Plants.

It’s also highly interdisciplinary research. “I’m trained in both the natural and social sciences and I integrate these various perspectives in the different projects that I do,” she says.

There are applied components of her research – which usually focuses on water issues, including water security governance – and more overarching work, “where I take a step back and look trends across many different fields of academic inquiry, from research to innovation.”

A digital revolution in environmental governance is underway, she says, which includes a transition from scarcity of data to the hyper-abundance of data, and new tools such as AI algorithms. These advances enable more real-time environmental monitoring, which means conservationists can more effectively detect, limit and even prevent environmental harm.

“For example, scientists have used digital bioacoustics to provide real-time location information for highly endangered North Atlantic right whales; this information is used to create mobile Marine Protected Areas in which ship’s captains have to slow down or avoid whale zones altogether. This reduces ship strikes, which were previously a significant cause of whale injury and mortality.”

“Another example is using satellites to detect methane plumes in real time. So we now know where the top methane emitters are in the world at any given time. And if there’s political will, we could even make the polluter pay in real time for so-called ‘fugitive emissions’ that were previously not tracked.”

But new tools, she notes, also come with risks. “Any technology can be used as a tool or a weapon. The same technologies I’m talking about could be used for precision hunting. So it’s very important that we create governance frameworks that constrain these risks, yet allow these technologies to be used for biodiversity protection and climate change mitigation.”

On winning the Guggenheim, Dr. Bakker says there’s something special about the award. “Academic work can sometimes take years to germinate,” she says. “And what the Guggenheim often does is highlight work that is just about to flower, to use a biological metaphor. And so I think the Guggenheim is also recognizing these long gestation projects that take a while to come to fruition but are truly trying to say something new and make both a scholarly contribution and a contribution to the public good or public knowledge. That, I think, is the lovely mix they have.”

Biomechanical engineer aims to build better aortic grafts

Marco Amabili, Canada Research Chair in Vibrations and Fluid-Structure Interaction in McGill University’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, is on a mission to develop devices to replace the outdated aortic grafts used today.

In 2022, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship in support of his work around the human aorta and aortic grafts – the prostheses used to replace a path of the aorta when there is a disease.

“What is used right now, honestly, is a bit old, dated. It was probably developed by people who were more interested in biocompatibility and some other aspects, but they completely forgot that mechanics plays a very important role in the human body. The graft presently used has many problems from the mechanical point of view.”

Dr. Amabili thinks it’s time for a new generation of these devices, especially since some people need them to survive. “And the quality of life is largely dependent on the quality of these devices,” he says. “So when we talk about improving one of those grafts, it means, for the future user, a huge benefit.”

The grafts currently used allow patients to survive, he notes, but they require follow up operations every 10 to 15 years. “And that’s already not fun, because it’s a big operation. So if you do something that does not require additional operations with time, or has no side effects, that would be a huge benefit for them.”

The scale of the challenge attracted Dr. Amabili to this area of research. “One of the reasons I started to get interested in this area, it was because it’s very challenging, very complicated.”

In addition to improving quality of life for patients, this work has significant economic potential. “Clearly, this type of operation requires huge resources in money and healthcare. And so imagine that instead of operating on a person once for life, you have to do it every 15 years, and you start when they’re 50 or 40. And also, if the quality of life becomes better, then the person is more active. So also, from the economic point of view, there are a lot of advantages.” Those economic benefits could include developing these improved devices in Canada.

Reflecting on wining the Guggenheim, Dr. Amabili says such awards are significant because they bring visibility to the researcher and the research. “That’s clearly important because then other resources can arrive easier, better graduate students can join your team – everything can be more successful.

University of Alberta researcher wins Nobel prize for Hep C discovery, now working on vaccines

It was the middle of the night on Oct. 5 when University of Alberta professor Dr. Michael Houghton learned he and his collaborators were the Nobel Prize winners in Physiology or Medicine for 2020. Dr. Houghton won the Nobel along with scientists Harvey Alter and Charlie Rice for their significant contribution to the fight against blood-borne hepatitis, a major global health problem that causes cirrhosis and liver cancer in people around the world.

Dr. Houghton said he tried to go back to sleep after the 3 a.m. call from a colleague but failed. “In the end I gave up,” he said in an interview with Adam Smith of Nobelprize.org. “And then… [I] got on email and there’s hundreds and hundreds of emails, which is all very nice of course.”

The three scientists discovered the hepatitis C virus (HCV), which causes 400,000 global deaths a year, in 1989.

After their discovery, protecting the blood supply from transmission was job one. The scientists quickly developed a blood test and by 1992 the virus was virtually eliminated from the blood inventory in the developed world.

Their attention then turned to therapeutics. “It took…the whole field and the pharmaceutical industry working for more than 20 years. But eventually, we’ve got these wonderful drugs now that can cure nearly everybody quite quickly and safely.”

Still, HCV remains a global epidemic. “So…the way eventually you have to control an epidemic like this is with a vaccine,” he said. “After many years of work, I think our field feels that it is now feasible…at the University of Alberta I’ve been working on an improved version that we think has a good chance of success, or at least being partially effective.”

Dr. Houghton was recruited to the University of Alberta in 2010 as the Canada Excellence Research Chair in Virology in the Li Ka Shing Institute of Virology. Two years later, he and his team developed a vaccine for the virus known to cause cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease and liver cancer. The vaccine is now in late-stage testing.

He is also leading an effort to produce a vaccine for COVID-19.

Dr. Houghton said he became interested in microbiology when was 17, “having read about Louis Pasteur’s life and his work, so he was my inspiration.” In terms of what drove his work, especially during years of frustration, he said it wasn’t the promise of awards or accolades. “It’s nice, but what counts for me more is that we’ve been able to prevent millions of hepatitis C infections that otherwise would have occurred through the blood supply. Prizes are very pleasant, but they’re only prizes. I’m much more happy when we can actually intervene with patients and prevent people from getting infected or provide a cure for them.”

Focusing on the nature and significance of art and the aesthetic

One of the foremost contemporary philosophers of art, Dr. Dominic McIver Lopes is a distinguished university scholar and professor in the department of philosophy at the University of British Columbia. His work focuses on the nature and significance of art and the aesthetic.

Dr. McIver Lopes has traced the value of images to how they extend the powers of human perception. His ground-breaking book Philosophy of Computer Art, for example, argued that computer art challenges some of the basic tenets of traditional ways of thinking about art and its creation. He is developing a theory of how aesthetic values guide agents engaged in a variety of aesthetic projects. The elements of his theory could yield novel insights into the origins of aesthetic practices and the foundations of aesthetic education. He is currently working on a book titled Being for Beauty: Aesthetic Agency and Value.

Dr. McIver Lopes holds a bachelor of arts from McGill University and a DPhil from Oxford University. He has been a fellow of the National Humanities Center and a Leverhulme Trust Visiting Research Professor at the University of Warwick. His awards include an American Society for Aesthetics Outstanding Monograph Prize and a Killam Research Prize..

Learn more about the Guggenheim Fellowship

* Dominic McIver Lopes is one of 24 Canadian winners of major international research awards in 2015 featured in the publication Canadian excellence, Global recognition: Celebrating recent Canadian winners of major international research awards

Creating new polymers for tissue regeneration

A professor of chemistry and biomaterials and biomedical engineering, Dr. Molly Shoichet was named North American winner of the L’Oréal-UNESCO Women in Science award for the development of new materials to regenerate damaged nerve tissue and for a new method that can deliver drugs directly to the spinal cord and brain.

An expert in the study of polymers for drug delivery and regeneration, Dr. Shoichet has been tackling the problem of the blood-brain barrier, a tightly interwoven network of cells that protects the central nervous system from toxins but can block helpful medications. Her novel solution is to deliver drugs in a gel-like polymer that can be injected directly into the cerebrospinal fluid and then remain near its injection point where the therapy is most effective. The team she leads has also created a polymer for the targeted delivery of drugs and antibodies in breast cancer.

Holder of a bachelor of science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a PhD from the University of Massachusetts, Dr. Soichet is a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Tissue Engineering and a university professor of chemical engineering and applied chemistry, chemistry and biomaterials and biomedical engineering at the University of Toronto. The recipient of many prestigious distinctions, she is the only person to be a fellow of Canada’s three national academies.

Learn more about the L’Oréal-UNESCO Women in Science award

* Molly Shoichet is one of 24 Canadian winners of major international research awards in 2015 featured in the publication Canadian excellence, Global recognition: Celebrating recent Canadian winners of major international research awards.

Measuring how human activity affects the Earth’s crust

University of Ottawa professor and geophysicist Dr. Pascal Audet was selected as a Sloan Research Fellow for pioneering a technique to measure how human activity affects the Earth’s crust.

An expert in earthquake seismology, Dr. Audet uses GPS data coupled with gravity variations obtained from the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment satellite to determine the extent to which large-scale human activity affects the deformation of the earth’s crust and to evaluate its impact on natural hazards.

Recently, his technique played an important role in an international study published in the journal Nature that showed the direct link between human-induced groundwater depletion and the uplift of California’s Sierra Nevada and Coast Ranges. This may increase the number of small earthquakes in the adjacent San Andreas Fault.

The fellowship will allow Dr. Audet to study the impacts of the oilsands in Western Canada.

Learn more about the Sloan Research Fellowships

*Pascal Audet is one of 24 Canadian winners of major international research awards in 2015 featured in the publication Canadian excellence, Global recognition: Celebrating recent Canadian winners of major international research awards.

Pursue research in physical oceanography

An assistant professor in physical oceanography, Dr. Stephanie Waterman has been awarded a Sloan Research Fellowship to pursue her research in physical oceanography.

In the department of earth, ocean and atmospheric sciences at the University of British Columbia, Dr. Waterman combines observational and theoretical oceanography to better understand how different components of ocean circulation, operating at different time and length scales, interact. She has been involved in a number of international observational campaigns in the North Atlantic, North Pacific and Southern Oceans.

Her Arctic research is organized in conjunction with the Canadian Arctic GEOTRACES program, an initiative to better understand biogeochemical processes in the ocean and improve projections of the ocean’s response to global change.

A graduate of Queen’s University, Dr. Waterman completed a PhD in physical oceanography at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She was a research fellow at the United Kingdom’s National Oceanography Centre, the Grantham Institute for Climate Change at Imperial College, London and the Climate Change Research Centre and Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science before joining the University of British Columbia in 2014.

Learn more about the Sloan Research Fellowship

*Stephanie Waterman is one of 24 Canadian winners of major international research awards in 2015 featured in the publication Canadian excellence, Global recognition: Celebrating recent Canadian winners of major international research awards.

Original contributions to number theory

Dr. Jacob Tsimerman has been awarded a Sloan Research Fellowship in Mathematics in recognition of his original contributions to number theory. An assistant professor in the University of Toronto’s department of mathematics, he also won the 2015 SASTRA Ramanujan Prize for young mathematicians.

Dr. Tsimerman works at estimating how many solutions there are to a system of polynomial equations using integers — whole numbers that do not have a fractional or decimal component. His work is rooted in the fundamental concepts of number theory and algebraic geometry. “He is one of the few mathematicians to have complete mastery over these two very different areas of mathematics,” notes the prize citation. “This has enabled him to achieve significant progress on a number of fundamental problems lying at the interface of the two subjects.”

Dr. Tsimerman holds a bachelor of arts from the University of Toronto and completed his PhD at Princeton University. Following post-doctoral work position at Harvard University, he joined the University of Toronto faculty in 2014.

Learn more about the Sloan Research Fellowships

Learn more about the SASTRA Ramanujan Prize

* Jacob Tsimerman is one of 24 Canadian winners of major international research awards in 2015 featured in the publication Canadian excellence, Global recognition: Celebrating recent Canadian winners of major international research awards.

Understanding how the brain is wired

Dr. Julie Lefebvre, scientist in the Neurosciences and Mental Health Program at The Hospital for Sick Children, was awarded a 2015 Sloan Research Fellowship in Neuroscience for her work to understand the fundamental mechanisms of how the brain is wired.

Dr. Lefebvre’s research involves studying the roles of genes in the complex formation of neural circuits. “I hope to bridge my work to advance our understanding of how genetic alterations affect brain development and other brain disorders,” says Dr. Lefebvre.

She aims to identify how nerve cells form specific patterns of neural connections that are essential for proper development and functioning of the nervous system. Her research will provide insights into how neural circuits assemble in a healthy brain, and how defects in these developmental pathways contribute to abnormal brain function and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Dr. Lefebvre received her bachelor of science from McGill University and earned her PhD at the University of Pennsylvania for research on neuromuscular development. She completed postdoctoral work at Harvard University, investigating molecular mechanisms of neuronal morphogenesis and circuit formation in the retina. She joined The Hospital for Sick Children in December 2013.

Learn more about the Sloan Research Fellowships

* Julie Lefebvre is one of 24 Canadian winners of major international research awards in 2015 featured in the publication Canadian excellence, Global recognition: Celebrating recent Canadian winners of major international research awards.

Improving our understanding of the immune system

A postdoctoral fellow in cell biology at The Hospital for Sick Children Research Institute, Dr. Vanessa D’Costa was awarded a L’Oréal-UNESCO Women in Science Rising Talent grant for her research into mechanisms that allow salmonella bacteria to escape the immune system.

Salmonella is one of the leading causes of food-borne gastroenteritis worldwide. Severe cases of salmonellosis can cause death and contribute to the development of reactive arthritis, an autoimmune disorder. Recent years have seen an increase in infections by drug-resistant salmonella.

Salmonella bacteria cause infection by evading the immune system with the help of toxin-like proteins called effectors, whose function is not fully understood by scientists. Dr. D’Costa’s research aims to determine how these effectors manipulate host cells and enable the pathogen to bypass the body’s disease-fighting systems. Her findings will provide insight into the functioning of other drug-resistant bacteria and, more generally, our understanding of the immune system.

Dr. D’Costa was earlier awarded a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research while completing her PhD at McMaster University and a Banting Postdoctoral Research Fellowship at the University of Toronto.

Learn more about the L’Oréal-UNESCO Women in Science International Rising Talent grant

* Vanessa D’Costa is one of 24 Canadian winners of major international research awards in 2015 featured in the publication Canadian excellence, Global recognition: Celebrating recent Canadian winners of major international research awards.

Unravelling the mysteries of the universe

Nobel laureate Dr. Arthur McDonald, professor emeritus at Queen’s University, and the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory (SNO) received the 2016 Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics “for the fundamental discovery and exploration of neutrino oscillations, revealing a new frontier beyond, and possibly far beyond, the standard model of particle physics.” The award was one of five given to experiments investigating neutrino oscillation.

In recognition for his research into neutrinos, Dr. McDonald was awarded the 2015 Nobel Prize in physics alongside the University of Tokyo’s Dr. Takaaki Kajita.

Dr. McDonald is the director of the SNO Collaboration that began researching the mysteries of neutrinos at the Sudbury site in 1984. The cavern that housed SNO has since expanded and morphed into a multipurpose underground physics facility called SNOLAB.

Sometimes called “ghost particles,” neutrinos are fundamental to the make-up of the universe, but relatively little has been known about them. Dr. McDonald’s team discovered the transformation of electron-type neutrinos to other types en route from the core of the sun to the Earth — a finding that expands our understanding of the sun and exhibits neutrino properties that go beyond the predictions of the Standard Model of Elementary Particles.

Dr. McDonald earned his PhD in 1969 from the California Institute of Technology and began his career at Queen’s University in 1989. He has been a professor emeritus since 2013, and holds the university’s Gordon and Patricia Gray Chair in Particle Astrophysics.

Learn more about the Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics

Learn more about the Nobel Prize in Physics

*Arthur B. McDonald is one of 12 Canadian winners of major international research awards in 2016 featured in the publication Canadian excellence, Global recognition: Celebrating Canada’s 2016 winners of major international research awards.

Demonstrating exceptional creative ability in the arts

An adjunct professor of English and former Barker Fairley Distinguished Visitor in Canadian Studies at University College, University of Toronto, Anne Michaels was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in Creative Arts for fiction. The author of five acclaimed poetry collections and two novels was also named poet laureate of Toronto in 2015.

Professor Michaels is an alumna of the University of Toronto where she later founded the long-distance creative writing program at the School of Continuing Studies. Her first book, The Weight of Oranges (1986), a volume of poetry, was awarded the Commonwealth Prize. She received the National Magazine Award, the Canadian Authors Association Award for Poetry and a nomination for the Governor General’s Award for her second collection, Miner’s Pond (1991).

Professor Michaels has written two novels. Fugitive Pieces was awarded the Books in Canada First Novel Award, the Trillium Book Award, Orange Prize for Fiction, the Guardian Fiction Prize and America’s Lannan Literary Award for Fiction. It was adapted into a feature film in 2007..

Her second novel, The Winter Vault, was a finalist for the Scotiabank Giller prize, the Commonwealth Writer’s Prize for Best Book and the Trillium Book Award.

Learn more about the Guggenheim Fellowship

* Anne Michaels is one of 24 Canadian winners of major international research awards in 2015 featured in the publication Canadian excellence, Global recognition: Celebrating recent Canadian winners of major international research awards

Tackling the toughest problems of quantum field theory

Perimeter Institute faculty member and adjunct professor at the University of Waterloo, theoretical physicist Dr. Pedro Vieira has earned a 2015 Sloan Research Fellowship for his explorations into the foundations of quantum field theory. He also won the prestigious Gribov Medal given by the Physical European Society to a young researcher in the theoretical physics fields of particles or quantum field theory.

At Perimeter, Dr. Vieira tackles the toughest and most long-standing problems of quantum field theory. He uses a mathematical technique called holography to translate questions about four-dimensional field theories into questions about two-dimensional string theories. That makes it possible for him to look at the questions through the use of integrability, a powerful mathematical technique for exactly solving two-dimensional theories. Holography then relates the solution in two dimensions back to a solution in four dimensions.

A graduate of the Universidade de Porto, Portugal, Dr. Vieira earned his master’s and PhD at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, France. He joined the Perimeter Institute in 2009.

Learn more about the Sloan Research Fellowships

* Pedro Vieira is one of 24 Canadian winners of major international research awards in 2015 featured in the publication Canadian excellence, Global recognition: Celebrating recent Canadian winners of major international research awards.

Unraveling a key evolutionary riddle

Professor in the departments of zoology and mathematics at the University of British Columbia, Dr. Michael Doebeli is “one of the foremost mathematical evolutionary biologists in the world and the main authority for theory on the evolution of organismal diversity,” says a statement issued by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. The foundation awarded Dr. Doebeli a fellowship in natural sciences in recognition of his research, which has led to a major change in how scientists understand the origin of new species.

The mathematical model Dr. Doebeli developed seeks to unravel a key evolutionary riddle: what factors underlie the generation of biological diversity both within and between species. His work has shown that new species can form in the absence of geographic separation, something once viewed as theoretically impossible. Dr. Doebeli has also provided new perspectives that have led to a unified understanding of the evolution of cooperation in nature.

Dr. Doebeli completed a PhD in pure mathematics from the University of Basel, Switzerland. He received the 2014 Research Award of the Canadian Applied and Industrial Mathematics Society, among other prestigious awards, and is a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

Learn more about the Guggenheim Fellowship

* Michael Doebeli is one of 24 Canadian winners of major international research awards in 2015 featured in the publication Canadian excellence, Global recognition: Celebrating recent Canadian winners of major international research awards.

Examining the history of Bolshevik eugenics

A historian of Russian medicine and life sciences, Dr. Nikolai Krementsov was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to carry out research on the interactions among science, medicine and literature in Bolshevik Russia (1917-1929). A professor in the Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology at the University of Toronto, he focuses on the history of international relations in science and medicine, especially during the interwar and Cold War periods.

Dr. Krementsov’s project is titled “I Want a Baby”: The History of Bolshevik Eugenics. In many countries, eugenics is often associated with genocidal race-purification programs. Not so during the Bolshevik Russia period, where it was based on a desire to improve the genetic fitness of the Russian people. But the movement failed to secure legislative support or spark an organized movement. After the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, however, it became an established scientific discipline, exerting influence on social policies. Eugenics was banned in the Soviet Union in 1930 under Joseph Stalin.