Implicit Bias and Selection: The Facts and Best Practices

“The selection committees for scholarships are objective.” To some extent, this is true. No one on a selection committee does their job with the intention to discriminate against a certain group. However, humans are still vulnerable to implicit bias.

Implicit biases are subconscious shortcuts our minds take to fill in the gaps about a person based on our background views. Our background views are formed from our knowledge, experiences, education, values, and environment. As a result, these views influence our choices and actions, often manifesting as “instinct” or “gut feelings”. For example, traditionally men are associated with power, initiative, and aggression, and historically leadership positions have been male dominated. This is why when presented with identical resumes, studies found that those associated with male names felt more qualified to be leaders than those associated with female names.

Our implicit biases can not only colour our views based on gender, but also based on age, race, or sexual orientation., Other studies looked at the relationship between ethnic or unique sounding names and the associated person’s likeability and likelihood of being hired. Applicants with ethnic sounding names and accents were viewed less positively than those without. When comparing unique names to common ones, researchers found that common names were the best liked and most likely to be hired whereas unusual/unique names were least liked and least likely to be hired. Russian and African American names were intermediate on this scale.

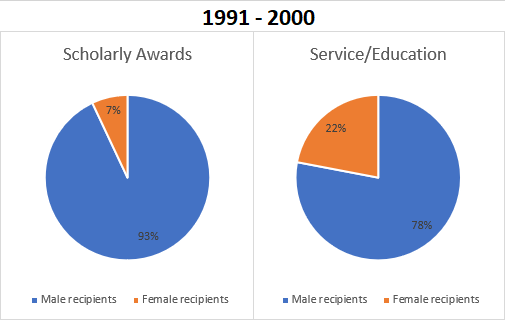

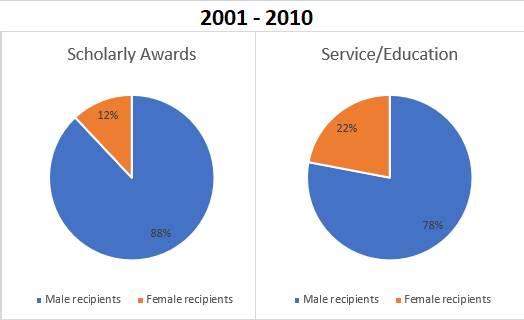

When it comes to science, research, high level leadership, and scholarly awards, women and people of colour are underrepresented. Unfortunately, there is very little research done on racial bias in the awarding of scholarly and academic recognition. In a 2011 study of awards recipients within the American Geophysical Union (AGU), researchers found that despite women making up 15-20% of AGU membership from 1999-2010, only 12% of scholarly awards were female. Compare that to the fact that 22% of service and education awards were given to women. A separate study published in 2018 observed that even though black investigators published the same number of papers as white investigators during their PhD and postdoctoral training, these papers received fewer citations. This study also found a gap in funding for Asian, foreign-born investigators which could indicate a bias against those with education or training from abroad. While the situation has improved in recent years, there is still a pronounced gap for some highly prestigious awards.

An example of a prestigious award that was found to have a notable lack of female representation among its recipients is the A.B. Baker Award for Lifetime Achievement in Neurologic Education. The award is particularly important in the neurology field because it involves a keynote-type of address to the members of the American Academy of Neurology. Recipients are acknowledged as leaders in the field and models for future neurologists. There appears to be a trend in female underrepresentation for awards that are associated with lectureships in which awardees can speak and offer their insights and vision for the future of the specialty. This means that in this field there is low visibility for women leaders and role models for future generations of women physicians.

These gaps are not the result of conscious decisions to discriminate, but rather the human need to stay within the realm of the expected. This need extends beyond the fields of science and research. These biases have an impact on who we choose to receive scholarships, whether we realize it or not.

What can you do to limit the influence of implicit bias on selection committees?

- Have a diverse selection committee. By including people of different racial backgrounds, religious backgrounds, genders, and life stages in your selection process, you can encourage equal consideration for underrepresented groups. However, it is important for all members to be educated in diversity and bias.

- Understand your awards program’s history with respect to discrimination or bias. Understanding the past helps make better informed decisions for the future. In this case, it can identify areas in which unintended bias may have skewed the type of people being nominated for or awarded certain scholarships. If bias is found, it is important to identify why and where the program is vulnerable to bias. Reasons can range from an unintended exclusion of a group from promotions to a reliance on objective judgements rather than structured quantitative evaluations.

- Encourage nominations from groups that are at a disadvantage due to implicit bias. People from minority groups are evaluated most fairly when the people of those groups make up at least 30 percent of the nominee pool. Encouraging nominations for people from underrepresented groups is the first step to having a fair evaluation of all the worthy award candidates.

- Provide checklists or structured evaluation forms such as rubrics. Implicit bias becomes a key factor in assessing applicants when evaluations are vague and based mainly on recommendation letters, so our pre-existing stereotypes fill in the gaps. Studies have found that having a structured evaluation system with clear criteria minimizes the influence of implicit bias.

- Discuss implicit bias and its effects with committee members before looking at applicants. Discussing the topic of implicit bias and its impact before looking at applications keeps it at the top of selection committee members’ minds. This increases the likelihood of members recognizing their own biases and making more fair, objective decisions. Learn how to outsmart your own implicit bias.

- Provide plenty of time to review applications and make decisions. Another factor that allows for implicit bias to impact decisions is time constraints. Given adequate time to carefully look at all applicants, selection committees are more likely to evaluate applicants on their achievements rather than how members feel about an applicant.

- Remove information that indicates or is about age, race, gender, or sexual orientation. This option is not necessary but removing any identifying information can ensure fair evaluation based solely on the quality of the application. However, this is not a replacement for properly educating selection committees on implicit bias.

- Avoid conflicts of interest. With Scholarship Partners Canada, reviewers are asked to identify personal, academic, or extra-curricular connections with a candidate. Upon confirming this, the applicant is reassigned to a different reviewer without a conflict of interest to ensure the evaluation remains objective.

Learning to recognize your own biases is an ongoing process and there are many resources available on spotting and avoiding implicit bias. Start here with eight tactics to identify and reduce your implicit biases.

Sources:

Bilimoria, D., & Lord, L. (2014). Women in Stem careers: international perspectives on increasing workforce participation, advancement and leadership. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Cotton, J. L., O’neill, B. S., & Griffin, A. (2008). The “name game”: Affective and hiring reactions to first names. Journal of Managerial Psychology.

Ginther, D. K., Basner, J., Jensen, U., Schnell, J., Kington, R., & Schaffer, W. T. (2018). Publications as predictors of racial and ethnic differences in NIH research awards. PloS one, 13(11), e0205929.

Holmes, M. A., Asher, P., Farrington, J., Fine, R., Leinen, M. S., & Leboy, P. (2011). Does gender bias influence awards given by societies? Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union, 92(47), 421–422. doi: 10.1029/2011eo470002

Leske, L. A. (2016, November 30). How Search Committees Can See Bias in Themselves. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/How-Search-Committees-Can-See/238532

Metcalf, H. (2017, March 8). Improving Recognition Through Awards: How to Mitigate Bias in Awards. Retrieved from https://www.awis.org/improving-recognition-through-awards-how-to-mitigate-bias-in-awards/

Purkiss, S. L. S., Perrewé, P. L., Gillespie, T. L., Mayes, B. T., & Ferris, G. R. (2006). Implicit sources of bias in employment interview judgments and decisions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 101(2), 152-167.

Silver, J. K., Bank, A. M., Slocum, C. S., Blauwet, C. A., Bhatnagar, S., Poorman, J. A., … Zafonte, R. D. (2018). Women physicians underrepresented in American Academy of Neurology recognition awards. Neurology, 91(7). doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000006004