Making Canadians care about science again

This op-ed was published on the iPolitics website on August 21, 2017

By James Woodgett, professor of medical biophysics, University of Toronto and director of research, Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute; and Jeremy Kerr, professor of biology, University of Ottawa

At some point over the past decade, Canada’s scientific community began to realize that the public support it had enjoyed in a previous generation was no longer guaranteed.

During the period of exceptional economic growth after World War II, researchers enjoyed broad support. Society knew that knowledge generation had value and, during a period of sustained economic expansion, was willing to fund research to make sure new discoveries kept on coming. The results are plain to see: Canada’s research community has made transformative advances, ranging from figuring out how pollution impairs water quality to developing a promising vaccine for Ebola.

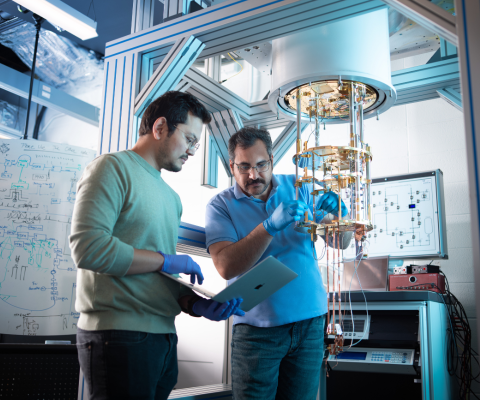

While the benefits of discovery remained obvious to scientists, the value proposition for Canadians has become less clear. Researchers themselves bear much of the responsibility for this. After all, Canadians fund most research grants — providing trainees with stipends and fellowships and supporting facilities with the sophisticated equipment needed to push into new frontiers. Meanwhile, researchers have become used to being closeted within their specialized fields, speaking to small numbers of like-minded experts using jargon-laden vocabularies, typically viewing the public from a distance. And then we ask for more funding.

Ultimately, decisions about whether Canada will embrace research as a priority investment depend on whether Canadians believe that research matters to them. And not just in an absolute sense, but relatively. The issue isn’t whether research benefits Canadians (I think we can all agree that it does) but how those benefits stack up against other priorities, like working toward Aboriginal reconciliation, maintaining Arctic sovereignty or improving healthcare services.

To make their case, researchers must make their findings more transparent and accessible. Publications should be available to anyone, not just privileged scientists with access to library journal subscriptions. Scientists must also be available and willing to discuss their work and what it means — to both specialized and general audiences.

Many researchers are working hard to shake off academic stereotypes, communicating with communities rather than simply lecturing to them. Whether it is working with primary school classes to raise butterflies, coaching high school science fairs, or working with and encouraging students from under-represented groups (as in the SciHigh program), there is a growing effort among researchers to illustrate the role that discovery plays in the life of communities.

Inspiring young minds to ask questions — to desire answers and to realize that there is so much more to learn about the universe — is key to both better education and a better society.

There is also a role for government to play in ensuring that Canada’s research funding mechanisms support transparency and accountability. The recent Fundamental Science Review commissioned by the minister of Science acknowledges that “great research ecosystems support public outreach, including efforts to engage citizens in research.” Recommendations coming from the review, including greater public reporting and outreach, will support increasing public trust in the scientific enterprise.

Research is in Canada’s interest, as it is for all progressive nations. Calls for increases in federal support for research have been carefully justified and target those holding the purse strings in Ottawa. But researchers neglect engagement with the public at our peril.

The benefits of such interactions are clear enough. Greater transparency in the research enterprise is likely to improve public confidence that researchers are using public funds sensibly, accompanied by recognition that discoveries can inspire people and help transform societies. If greater societal engagement also leads to the end of ivory tower thinking by researchers, institutions and granting councils, so much the better.

-30-

About Universities Canada

Universities Canada is the voice of Canada’s universities at home and abroad, advancing higher education, research and innovation for the benefit of all Canadians.

Media contact:

Lisa Wallace

Assistant Director, Communications

Universities Canada

[email protected]

Tagged: Research and innovation

Related news

-

Urgent action for our publicly-funded universities critical to Canada’s economic stability and growth

-

Outstanding discoveries by Black researchers in Canada

-

Universities are advancing technology through international partnerships

-

Global university partnerships are finding solutions to the climate crisis